The accountability gap (officials summoned for questioning #NationalAssembly’sCommissions)

-

Recently Browsing 0 members

- No registered users viewing this page.

-

Topics

-

-

Popular Contributors

-

-

Latest posts...

-

524

Do you know your wife/girlfriends body count?

See you don't understand personality profiling. 80 failures is a lot. You need a deep thinking serious type. Rare amongst women. -

62

Tourism Thailand Delays Tourist Entry Fee Amid Travel Concerns

Shock Horror! Thailand isn't going to put the price UP for once when they have less customers! -

16

Russian soldiers poisened by bottled water sabotage op

Until they lose the war, which they are now losing, and surrender. After which time the war crime trials begin. To the winner goes the spoils. -

53

Economy Thailand's Digital Baht Plan Targets Big-Spending Tourists

Does this mean that tourists, who are not allowed to open a Thai bank account, will be given the opportunity to "create accounts with licensed digital operators under strict regulation from the SEC..."? I have a feeling that by the time the "Adherence to stringent anti-money laundering checks via Know Your Customer (KYC) protocols" is completed, the tourist's three-week holiday will already be over. -

5

Is Tax my Responsibility, can my UK company ask to pay UK tax?

Do you have an employment contract with the UK company? Are you totally freelance? Could you not simply invoice the UK "employer" for your services? I -

2

Trump Fires Maurene Comey, Epstein's Prosecutor

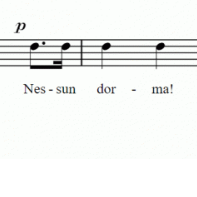

NEW HIT SONG - Releasing the Files (Trump's Epstein Files Saga) Lean back and enjoy

-

-

Popular in The Pub

.thumb.jpeg.d2d19a66404642fd9ff62d6262fd153e.jpeg)

Recommended Posts

Create an account or sign in to comment

You need to be a member in order to leave a comment

Create an account

Sign up for a new account in our community. It's easy!

Register a new accountSign in

Already have an account? Sign in here.

Sign In Now